Image: Amsterdam Diamond Industry – Het Parool

Amsterdam was once the centre of the diamond industry. The exhibition Amsterdam Diamond City tells the history of this Amsterdam diamond industry, which was the first in the Netherlands to deal with a trade union.

A total of thirteen diamond workers at an Amsterdam workshop, looking into the lens of the camera around 1913. On the left of the photograph are the so-called adjusters, with their faces to the window. On the right are the polishers, with their backs just facing the window.

“This causes the light to fall over the back of the polisher onto the diamond, so that they are not blinded,” says cultural historian Daniël Metz, who was responsible for the design of the exhibition Amsterdam Diamond City in the Jewish Historical Museum. “A workshop was also preferably built on the north side. For a diamond worker it is the matte light that is important, not the sharp southern light.”

The Amsterdam diamond trade reached its peak between 1900 and the First World War. The city had more than eighty diamond factories, where about ten thousand Amsterdammers worked. “The diamond trade was the cork on which the Jewish community floated. Jews had nowhere else to go. They were not allowed to join guilds in the past,” says Metz.

Most Jewish families in Amsterdam were somehow dealing with diamonds. Seventy percent of the people who worked in the industry were Jewish.

The Nieuwe Achtergracht was the heart of the diamond industry. There were various diamond factories there. On the nearby Weesperplein two diamond bourses were inaugurated in 1911.

King of the Amsterdam diamond trade

“For many Jews, the diamond industry was the way out of poverty. In the nineteenth century, the Asscher family lived in the Bussenschuthofje, a slum on the Rapenburgerstraat. The family let a son learn the trade from a master in the diamond factory. They paid for this for two years until their son was allowed to call himself a polisher and to work independently.”

In 1906 their son started his own factory in the Tolstraat. Metz: “Asscher was the king of the diamond trade. The company is still in the building, but it doesn’t polish anymore.”

The working conditions in the diamond polishing factories were bad. Under the leadership of Henri Polak, former municipal councillor and son of a Jewish brilliant polisher and Kattenburger Jan van Zutphen, the Algemene Nederlandse Diamantbewerkers Bond (ANDB) was founded in 1894. It was the first professional trade union in the Netherlands.

The union introduced a holiday week in 1910, an eight-hour working day in 1911 and a forty-hour working week in 1937. Diamond workers were required to be members. In exchange, they were paid in the event of a strike, unemployment or illness. In the Henri Polaklaan stood the trade union building, designed by Hendrik Petrus Berlage. At the end of the First World War the trade union had ten thousand members.

In addition to working conditions, the ANDB also devoted itself to the cultural development of its members, so that they could compete with the ‘possessing class’. There were music and singing societies, reading clubs and theatre companies. A library was founded on the upper floor of the union building under the motto ‘Knowledge is power’.

Metz: “The library had many politically committed and enlightening books. Polak fought for equality. There were many theatres in the Plantage area. Plancius on the Plantage Kerklaan of the Jewish vocal society Oefening Baart Kunst was one of them.”

British crown jewels

Before and during the heyday of the diamond industry, Amsterdam’s factories polished famous diamonds. Company Mozes Elias Coster polished the Koh-i-Noor in 1852 and Joseph Asscher of the firm I.J. Asscher polished the Cullinan in 1908, the largest diamond ever found in South Africa. Both stones were given to the English royal family and are part of the British crown jewels. A replica of the British sceptre of crystal glass can be seen in the exhibition.

Furthermore, there are attributes of the diamond trade, including cutters, cutting materials, scales and a suitcase of diamond cleaver Elias Spitz with a cleaver knife and a special bowl. There are models of a polishing shop from 1840 and the workshop of Asscher and there is a brooch with the image of King William III, made by the firm Coster.

Strong reputation

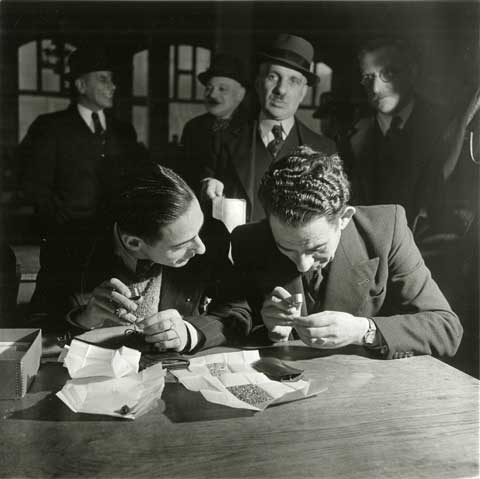

The exhibition also pays attention to the years of occupation. Jewish diamond traders were forced to hand in their stones by the occupying forces in April 1942. Eventually, the traders were deported. NSB photographer Bart de Kok recorded the robbery of the diamond dealers. Nine photos at the exhibition show how Germans were grabbing into the pockets of the Jews at the Diamond Exchange in Weesperplein.

The occupation was the final blow to the Amsterdam diamond trade. Only a small number of manufacturers survived the war and resumed work, including Asscher, Moppes and Henri Soep. Amsterdam was no longer able to regain its leading position. This was taken over by Antwerp, New York, Tel Aviv and Mumbai. ‘But her reputation as a centuries-old diamond city lives on,’ according to a text in the exhibition.