We are back with the second part of our blogpost series on the poignant history of Jews in Poland. If you missed the first part, I invite you to discover it [here]. Let’s now dive into the continuation of this epic tale, specifically focusing on the “Escape Movement.“

It was a summer in 1946, in Kielce, a city in Poland. Picture a scene of unspeakable cruelty, a pogrom in broad daylight. And the most shocking part? All of this unfolded right in front of the local police. Some even whisper that they took part in it.

Jews, who had miraculously survived the German occupation, met their end in this city, killed by Poles. Over 70 of them perished. The government, powerless, could do nothing to prevent this tragedy.

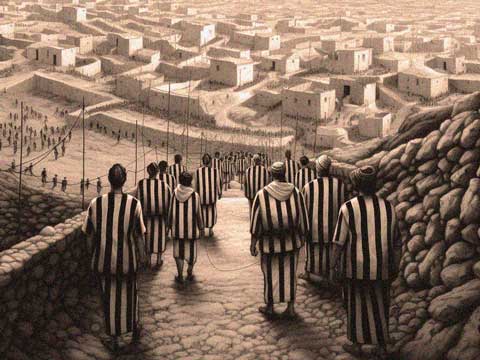

The echoes of this violence resonated throughout the country. Jews who had hoped to return and rebuild their lives in Poland were brutally brought back to reality. After Kielce, there was only one option left for the Jews of Poland: to flee. This is how the great “Escape Movement” (bericha) gained massive momentum.

End of several centuries of coexistence

This movement began as a spontaneous reaction from certain groups of survivors. During the German occupation, they had already realized that the Holocaust marked the end of several centuries of coexistence between Jews and other inhabitants of Eastern Europe.

Abba Kovner and a group of surviving fighters from the Vilna ghetto were convinced of this. As were a group of Jewish partisans led by the Lidovsky brothers, hidden in the forests near Rovno, in Volhynia. While assisting survivors, these groups sought to establish contact with representatives of the Mossad le-Aliyah Bet in Romania, hoping to create an escape route to the Mediterranean.

Their efforts bore fruit, and their activities centralized in Lublin, where the provisional communist government of Poland was based. By a fortunate coincidence, they also managed to contact a third group of 300 to 400 halutzim (Zionist pioneers), mainly members of the youth movement “Hashomer Hatzair.” These youths, having fled to Soviet Asia at the start of the war hoping to reach Eretz Israel, eventually found themselves in Lublin, driven by the same hope as the other two groups.

Israel was not just a refuge

In January 1945, surviving leaders from the Warsaw ghetto arrived in Lublin: Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman, Zivia Lubetkin, and Stephan Grayek. The youth, as always in times of upheaval, took the initiative. They took the reins, determined not to rebuild their lives on the ruins of the past. For them, Eretz Israel was not just a refuge, but the only place in the world where a Jew could control their own destiny. The Zionist youth movements took charge of organizing this spontaneous immigration, convinced that the fate of their people was in their hands.

But disagreements arose. Abba Kovner wanted to leave immediately for Eretz Israel, while Yitzhak Zuckerman believed they should stay in Poland to help Jews escape. Kovner continued his journey to Romania, then Italy and Eretz Israel, while Zuckerman and his supporters remained in Poland.

Initially, the “Escape Movement” was modest, but after the Kielce pogrom, everything changed. The movement became semi-legal. Between 75,000 and 100,000 Jews managed to leave Poland.

Germany… a refuge?

Ironically, Germany became a refuge for Jews. In 1945, after the revelation of the horrors of the concentration camps, the Western world was in shock. The liberated camps housed about 60,000 Jews. Some were already beyond any hope of rescue. After liberation, survivors began searching for their families. Many joined the “great migration” that took place in Europe in the summer of 1945. But for most survivors from Eastern Europe, returning home revealed a tragic reality. Eastern Europe rejected them. Homeless and family-less, they returned to the very camps they had left.

In 1945, David Ben-Gurion, president of the Jewish Agency, visited the camps in Germany. For the survivors, he was a symbol of hope. Ben-Gurion saw in these survivors a historic opportunity for Zionism. He believed that the Jewish DPs in the American occupation zone could influence the American government to open the doors of Eretz Israel to Jewish immigration.

The “Escape Movement” would not have existed without the will of the survivors. The yishuv provided this movement with its organizational skills, economic resources, and the leadership of its youth. This combination led to the creation of the Jewish state. In 1946, the needs and aspirations of Jewish refugees aligned with those of the Zionist movement. The fight for a new life coincided with the struggle to create a Jewish state.