There are few greater Jewish compliments than to call someone a mensch … although a real mensch would of course be too modest to want to receive a compliment.

A mensch is a person on whom one can trust to act with honor and integrity. But the Yiddish term means more than that: it also suggests someone who is kind and attentive.

Rabbi Neil Kurshan, author of the book ‘Raising Your Child to be a Mensch‘, characterizes it as “responsibility fused with compassion, a feeling that one’s own personal needs and desires are limited by the needs and desires of other people. A mensch acts with self-control and humility, always sensitive to the feelings and thoughts of others“.

A mensch is driven by an innate decency, perhaps motivated by a sense of values to live by, but not out of appreciation for recognition. They will behave like a menschg at times when it can be difficult to be one. In the Ethics of the Fathers, Rabbi Hillel said, “In a place where there are no men, try to be a man. Read man here as a mensch.”

It sounds like a masculine term, but it comes from the German word for “human being“. So a woman can also be a mensch.

Jonathan Hadary, who played Tevye a few years ago in a 50th anniversary revival of Fiddler on the Roof in the United States, found the world’s most famous milkman a kind of mensch. “He’s a beautiful, smart, cunning, restless, good-humored, sweet, loving, open-minded man,” said the actor.

A mensch may be someone who has achieved high office with a lot of public responsibility, but they are also largely unsung heroes or heroines, admired within a small circle that knows them well.

Walk in God’s ways. The connection between the philosophy of Jewish faith and the mensch.

A boy used to start his bar mitzvah speech with the words, “Today I’m a man.” What does Judaism have to say about being an adult? The answer can be summed up with the Yiddish word mensch, “a decent man.”

What should we do? What are we supposed to do? Something that is both simple and immensely complex – to be a mensch, a caring, ethical human being.

Maimonides (the great medieval Jewish thinker) gives – at the beginning of his code, the Mishneh Torah – the most important guideline: ve-halakhta bi-drakhav, “you must always walk in God’s ways“.

As the rabbis said: “Just as God is kind, so you must be kind; just as God is merciful, so you must be merciful; just as God is holy, so you must be holy“.

Maimonides says: “There are many different attributes. One person is temperamental and always angry, the other is very even and never angry, one is arrogant, the other humble, lustful or pure, etc.“.

For Maimonides, the right way, God’s way, is the middle way. We should “not be easily angry but also not be like a dead man who doesn’t feel“.

We must try to live a sober life. “Don’t lust, except for those things your body needs, without which you wouldn’t be able to live. Don’t become obsessed with your work. Remember, its basic purpose is to secure the necessities of life.” How do we reach this middle way, the way of balance? We have to repeat a measured reaction over and over again until it becomes part of us.

Illness as an imbalance

Maimonides uses the image of a sick person to explain why we are not all following a measured path. When we are sick, our senses are distorted. We perceive the bitter as sweet and the sweet as bitter. We want to eat things that are not good for us. So do souls when they are sick. They desire and love bad ideas, and reject what is healthy, the right path. It is easy for them to continue the way they have done, even if it has been bad for them.

Maimonides outlines a method of change through behavioral change. He believes that if a person has an extreme quality, such as stinginess, that person should behave in a way that is the opposite – that is, be very generous. One extreme will uproot the other and the person will be able to follow the middle path.

Maimonides understood that motivation is the key to all our actions. We can suffer for a long time, not because we strive not to be angry, but because we are passive. While a rabbinic proverb says, “Who is rich? A person who is content with his fate,” Maimonides knew that complacency could also be an excuse for laziness.

Maimonides adds: “In your search for the middle way, to avoid lust or jealousy, don’t say that you won’t eat good food, or that you won’t marry. This is a bad way… Someone who follows that path is a sinner“. The Talmud teaches, “Isn’t it enough for you what the Torah has already forbidden, that you have to want to forbid extra things for yourself?”

The vision of Maimonides is only one vision of “the path of God” on which we are called to travel. Even within the Jewish tradition there are other models.

A Chassidic image of the mensch

In chassidism, for example, man is experienced as more dynamic. Therefore, a golden mean is not only an impossible goal to achieve, but perhaps not even the right goal.

Instead of looking for the perfect balance between opposing qualities, the Chassidic model increases our ability to make the right choice in a given circumstance. This is more in line with the words of Ecclesiastes: “There is a time and place for every thing under heaven. A time to be born and a time to die… a time to love and a time to hate…”

In this model there is a time to be angry and a time to calm down, a time to be generous and a time to hold back.

But in the hustle and bustle of real life, we tend to abolish the choice and instead act in a routine that originated from our past. So the task is to try to see clearly, to be conscious, to avoid the kind of confusion described by Isaiah as: “Ah, those who call evil good and good evil, who present darkness as light and light as darkness.”

In the story of creation, God’s first act is to separate light from darkness. And yet we can only see light through the contrasting darkness. We live our mortal life knowing that darkness inevitably follows light. Both light and darkness are necessary, and together they help us see.

What is the most important verse in the Torah?

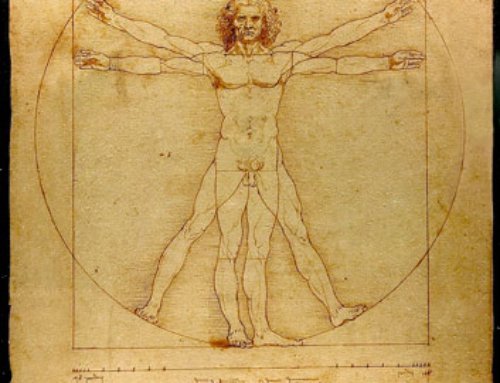

Rabbi Akiva said: “You will love your neighbor as yourself“. This is a great principle of the Torah. Ben Azzai didn’t agree with this: the verse “This is the book of the descendants of Adam… the man who God made in God’s likeness” expresses for him an even greater principle.

Why does Ben Azzai find such an obvious choice as “love your neighbor as yourself” insufficient? Perhaps, quite simply, because some people do not know how to love themselves. Maybe because it asks too much of us to love everyone? Or maybe Ben Azzai thinks that the simple explanation of human existence is enough: “This is the account of Adam’s descendants.”

For if we look into the face of another man, we see before him the image of God, the image of all God’s creatures that ever existed. In fact, we look in a mirror and see our own face in it. Through the awareness that we are all equal, both in our humanity and in the fact that we were created in the image of God, we learn to treat the other with respect and kindness.

And isn’t that just the essential characteristic of a mensch?